While it has been encouraging to see the various investments the Township of Langley is making to make our streets safer, as well as attempting to catch up on much of the missing infrastructure and community facilities caused by the development subsidy component of Willoughby’s development model, the elephant in the room is the ballooning levels of debt being accrued.

The Langley Advance Times recently published this article on how the Township's debt has risen from $168 million before the 2022 elections, to $668 million1. After seeing the article, it felt like an appropriate time to look at why this rapid borrowing has happened and what it means for our community. What led us here, and what different approaches could create a more stable financial future?

The Suburban Growth Model

I personally believe the Township of Langley’s transformation into a suburban community began in 1979 with the opening of Willowbrook Mall. Although I haven’t been able to confirm this in any news sources from the time, I have been told that as part of the deal to build the mall, the owners/developers agreed to pay for the construction of the sewer line and pumping stations from the mall all the way north up 200 Street. They even paid for the new sewage treatment plant at the other end, situated along the Fraser River. In the Administration Committee’s section of the 1979 Stewardship Report, Mayor George Driediger certainly seemed happy with the mall’s arrival after “long negotiations.”

Around the same time, and continuing into the 1990s, we saw the development of Langley Meadows, Walnut Grove and Murrayville which promised to bring in more taxpaying residents. The location chosen for Walnut Grove - known at the time as Area E - was largely due to the proximity of the aforementioned treatment plant, and because Genstar Development Company already owned a large 160 acre parcel in the area.

However, in 2000s and 2010s, the infrastructure in those older areas was starting to reach the end of its life. There were other mistakes along the way too - areas of non-ALR land outside of Metro Vancouver’s urban containment boundary became rural suburbs which demanded the upkeep of paved roads, water service, and potentially now even garbage collection, adding more strain on top of the budget to provide maintenance and services to these sprawling distant areas.

While there was a movement towards planning for denser, more cost-effective, urban style areas in Willoughby, with less land used on setbacks and more townhomes and mid-rise apartments added in to the mix, the problem is there was never a meaningful effort to stop using the suburban planning and growth model.

Instead of going back to these older neighbourhoods to try and encourage some more density or investment to help cover growing infrastructure costs, developer charges were instead frozen at low rates for 12 years between 2007-2019. This resulted in lots of rapid new greenfield development. My interpretation is there was an idea that this growth would help cover the replacement cost of roads and other infrastructure elsewhere with additional property tax revenue and make the township more financially sustainable overall. Unfortunately the low development fees resulted in inconsistent, unfinished and patchy infrastructure, and minimal community facilities which needed to be addressed.

Today, it’s 200 Street 2040, where instead of suppressing development charges (these have now been significantly increased), this time the “developer bait” is in the form of hard infrastructure, a promised Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) line. While it might seem like we are living under a brand new approach, seeing all these new improvements and projects being completed everywhere, underneath the new bodywork it’s the exact same model.

It’s fairly clear that over the years, many councils and staff have been starry-eyed by the prospective wealth and benefits brand new planned growth might bring to the community. The only difference this time is we’re not waiting for that money (or even the BRT line!) to come through, we’re front-loading these ideal future outcomes with debt. The debt - most of which has been earmarked to be paid back with future development fees - is being used to pay for a whole array of projects, from road widening, new facilities, and other projects appearing more for prestige than just meeting community needs.

Higher levels of borrowing have been seen as more politically acceptable in recent years as many see this as necessary to address Willoughby’s long-standing shortfalls and needs, however its use goes far beyond that.

It’s clear that the promise and idea of a large influx of money from growth has given those in charge the confidence to take on excess amounts of debt, and even worse, this confidence has also relieved pressure on the municipality to rethink the suburban approach to infrastructure planning, so there has been a continuation (and acceleration, funded with debt) to build new excessively wide roads and ignore (and even try to reject) zoning reforms for more urban infill in existing areas.

This is a pattern that has repeatedly failed from a financial perspective. The first suburban areas of the Township, which were supposed to grow the tax base, are not financially self sustaining. Next, Willoughby was developed to help cover those costs, but that required cut-price development fees, which left Willoughby with a whole host of expensive problems to fix as well. Now the goal is to create 200 Street 2040 as a new gold mine, but that gold is being spent before it has even been dug out the ground.

The Illusion of Wealth

Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns has worked with many cities as a consultant, both before and after the formation of Strong Towns in 2008. In this presentation he gave in 2023 in Medicine Hat, Alberta, he tells us what he has observed the first thing cities will do when they have financial trouble. Can you guess what it might be?

The answer is not “debt” as you might expect, but rather that cities will try to grow faster, and this is what we have observed in the Langley Township. It is, regrettably, a very common trap, and often fallen into by well-meaning people in local governments across the country.

He explains how this development model “provides all the illusions of wealth and prosperity in the short term, and all the costs and drag of irresponsible government in the long term.”

And that is the problem, it is, what Marohn calls, the illusion of wealth. The amount of money brought in can appear much greater than it actually is in reality, and may not break even over the long term.

Willoughby itself is a great example of this. Right now we are picking up the pieces from over a decade of frozen developer fees, and it’s going to cost millions of dollars. Even with the now higher development fees, we're still likely not collecting enough taxes to cover the true long-term cost of infrastructure maintenance and replacement of what is being built. There’s certainly no indication that it’s being considered or factored in to these calculations.

The development charges might cover the initial construction, but they don't account for the decades of maintenance, operational costs, and eventual replacement that the Township will be responsible for. Every new subdivision adds kilometres of roads, water lines, and other infrastructure that will need to be maintained and replaced, creating future financial obligations that far exceed the one-time development fees collected today. We're essentially creating new long-term liabilities while using debt to solve our current infrastructure deficit.

As the urbanized area grows there are more roads to clear of snow, more fire stations to build, more water pumping stations and reservoirs to be constructed.

After 25-30 years, all the roads will need to be replaced, in 50 years the water pipes will need to be replaced, as well as all the other ongoing infrastructure maintenance, repair and replacement costs.

And finally we come back to those prestige projects mentioned earlier, such as the promised $154.7 million2 Smith Athletic Facility. Part of the reason is good intentions - it’s understandable to want residents to enjoy world-class facilities (and this can also make it difficult politically to oppose them). It may not even seem like much more expense either, the initial cost is maybe about double what a conventional park would cost.

But a large factor in why these elaborate projects are approved is to help “market” the area to developers and residents to again help boost that growth. This means extra money is being spent to make it grander and more desirable, only to then try and collect it back again later from fees. This ignores the reality that the local government is responsible for the staffing and ongoing upkeep of a now larger more complex piece of infrastructure indefinitely.

(That’s right kids, a stadium isn’t just for Christmas, it’s for life.)

Real Wealth

So if outward growth is just an illusion of wealth, what is the true wealth of cities?

Real wealth comes from making the most of what we already have - our existing neighbourhoods, infrastructure, and community assets. As we’ve mentioned before, developers and existing property owners will build in these desirable places without needing encouragement or a subsidy, as it is a proven place. They already know people want to live here and want to have access to everything the neighbourhood has to offer.

As places build up, they begin to generate more in tax revenue than they cost to service and maintain. These are the denser areas where infrastructure has been fully paid off, buildings have been incrementally improved over time, and the compact development pattern means services can be provided efficiently.

Think of somewhere like New York City - nobody came along one day and planned it out and decided where each skyscraper would go and which street corners would have a bodega - it was built up over time through human collaboration and all that effort and investment was driven by it being a desirable and successful place people wanted to live.

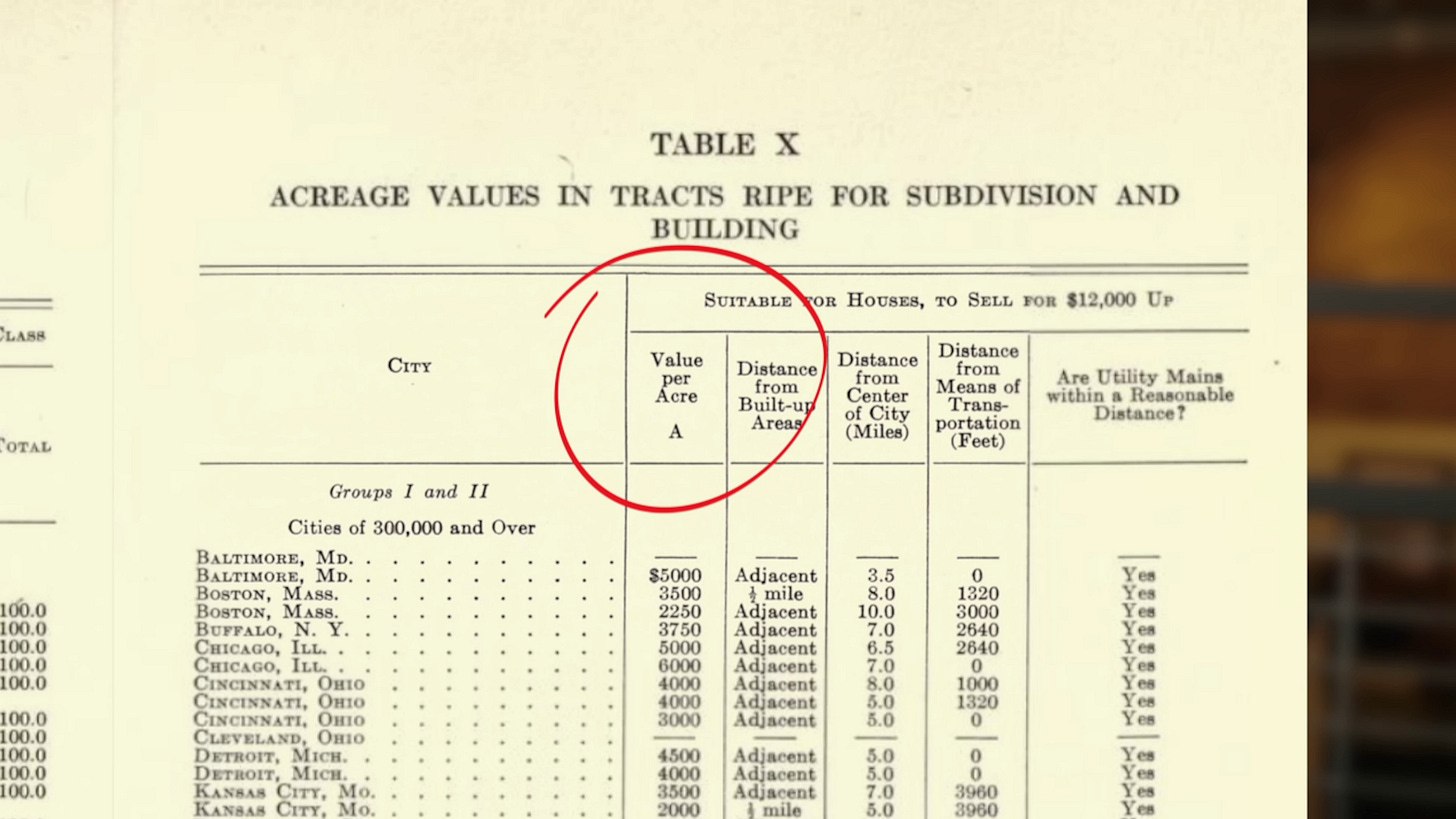

Strong Towns and other institutions like Urban3 measure this wealth in value-per-acre. Essentially how much tax revenue received from each acre of land. This isn’t a new concept either, in early 20th Century planning books, such as Neighborhoods of Small Homes by Harvard University Press in 1931, subdivisions in different cities are graded based on their value-per-acre.

In my opinion we have some of the nicest and best neighbourhoods in Metro Vancouver, and these have huge potential for more financially sustainable growth within them.

Some aren’t quite delivering enough value-per-acre to sustain their own infrastructure and municipal needs in the long-term, what is known as the cost-per-acre. You can see this for yourself on our own, currently rather primitive, value-per-acre map.

We also have the historic areas of Fort Langley and Aldergrove built in the traditional development pattern that already lend themselves well to a high value-per-acre built form.

One of Strong Towns ideas is the private-to-public investment ratio. In a financially sustainable community, Marohn believes the total value of private property should be at least 20 to 40 times greater than the public infrastructure investment needed to serve it. In simpler terms, for every dollar the municipality spends on infrastructure, there should be at least $20-$40 of private investment generating tax revenue to support it.

In areas which are lagging behind, incremental, small-scale improvements can help improve this ratio. When a local business owner adds a second story to their building, when a homeowner converts their garage into a rental suite, or when a vacant lot becomes a small mixed-use development - these modest changes compound over time.

Areas that can evolve over time - adding density where it makes sense, accommodating new uses as needs change, and allowing for organic growth - are more resilient to economic shifts than areas locked into a single pattern of development. This, of course, goes counter to every suburban planning textbook.

A New Way

In this first part of this two part piece, I have tried to list out the “why” Langley Township needs to change our development/growth plan from a financial perspective. It is not intended as an attack on any of the decision makers of today or the past. I believe these leaders, past and present, believed that what they are doing is good and right and best for the Township of Langley. These are common traps, and the ideas around this model are so widespread many of our engineers, planners, staff and elected officials might not think to question it. But unfortunately for them, and us, it is fundamentally flawed, and can lead to errors in judgement.

In Part 2, I will lay out a “white paper” on what Langley Township needs to do to find out its financial situation and help break out of this pattern. From more value-per-acre analysis, to infrastructure reports, to new allowed forms of construction, we have the tools to move towards something far more sustainable in the long run.

Stay tuned!

Much of the debt is pending approval from the Ministry of Municipal Affairs, which can take months/years, and also may not yet have been drawn down.

Based on the projections in the article, dated March 9, 2024.