Proactive, not reactive, urban planning

We habitually reach for bandaids to cover our poor planning decisions

As I discussed a while ago in my proposal to “complete” Gloucester Estates, when we create commercial areas and industrial areas far away from where people actually live, it means people inevitably have to drive to get around. Allowing this creates car-dependency and a reliance on road infrastructure.

In many municipalities, not just Langley Township, again and again we make these same kinds of mistakes, and we continue to encourage it to happen with how we plan and build communities.

Induced Sprawl

Last year, the City of Mission Council approved Cade Barr Business Park. On the website for the business park, they explain one of the primary reasons this site was chosen is because the Mission 2050 Transportation Plan calls for widening the roads that lead to the site - Stave Lake Street and Dewdney Trunk Road.

This is a classic example of how widening roads induces not just demand, but also sprawling forms of planning. Just the announcement of road widening, which makes it easier for more cars to get to a more distant location, led to the proposal and approval of more sprawling development.

It also shows how reactive planning becomes when we default to car infrastructure. Instead of thoughtfully considering where development should go based on existing infrastructure capacity and long-term financial sustainability, we're essentially letting road expansion plans drive our land use decisions. This backwards approach means we're constantly playing catch-up, building more roads to serve sprawling development, which then requires even more infrastructure investment to maintain, creating an expensive cycle that not only many municipalities simply can't afford long-term, but also creates worse, more pedestrian hostile communities.

From this angle, I perceive wider and wider arterials and larger and larger parking lots as basically bandaid fixes. Fat arterials and road widening are a symptom of scattered development where good city planning has been hindered by a number of forces; a single-use zoning regulatory framework, a lack of time and resources given to planning, lack of community involvement in the urban development of a place, outdated road engineering practices, and kowtowing to the demands of the real estate development industry.

The Right Way

We can see the evidence that this is not “the right way”, by looking at places locally and around the world where planning has been given the time and attention it deserves. In Houten in the Netherlands, a city with a population of 50,000 people, the “figure 8” arterial ring road is the only major road in the entire town, and is just 2 lanes for most of its length. In Seishinminami New Town in Japan, most of the arterial roads are just two lanes, even adjacent to high density residential buildings.

When communities are planned well, with shops, jobs, schools and transit within walking distance, often 2 lane arterials are all you need, and when roundabouts are used, they can move even higher volumes of traffic continuously.

What's particularly frustrating is that we already know how to do better, even within our existing regulatory framework. East Clayton in Surrey is a perfect example, this entire neighbourhood was planned using a charrette process that brought together planners, engineers, and community members to design a complete community from scratch. The result? A neighbourhood of over 15,000 residents that functions perfectly fine without a single multilane arterial road running through the middle of it. The parking concerns often brought up by residents in Clayton illustrate just how many cars are still present in the neighbourhood, but no multilane arterials are required due to a porous street grid, use of roundabouts, and amenities within walking distance.

It’s also clear just from observational evidence that many road widening projects Langley Township is embarking upon are often just wholly unnecessary. As of writing, 80 Avenue in Willoughby has been closed 2 weeks as part of a project to widen it to 4 lanes, and since I live relatively near by, I have driven around the area myself during peak times. My observation is this closure and loss of a key arterial route has not resulted in more traffic congestion. This project doesn’t solve congestion since there’s no congestion to solve! Instead their existence will simply promote more car use and subsidize sprawl that can’t pay for itself long-term.

Just as we understand that adding wider roads induces demand, closing roads can cause local traffic to evaporate and improve. I invite you to drive around the area and ask yourself the question, does this need to be four lanes? Should we be spending $10,500,000 (plus the increased ongoing maintenance costs) to widen this road from 204 Street to 212 Street?

We also have to talk about safety. This study outlines how the lack of access control combined with existing driveways and intersections will likely increase total crash frequency compared to the current 2-lane configuration. Multilane arterials with driveways experience higher crash rates due to multiple conflict points from lane changes, turning movements, and driveway access. The widening will also create new crash types that don't exist on the current 2-lane road: rear-end crashes from vehicles changing speeds between lanes, sideswipe crashes from frequent lane changes, and more complex pedestrian conflicts as people must cross four lanes of traffic instead of two, as outlined in this study.

Residents may be expected to feel grateful for these “improvements”, but those who live on these roads suffer with more traffic pollution, noise and a larger barrier to cross. They are symbols of waste caused by poor planning and repeated failures to make communities livable without a car. And of course, the taxpayer is burdened with the ongoing costs to fix potholes and resurfacing costs for double or triple the amount of asphalt that was there than before.

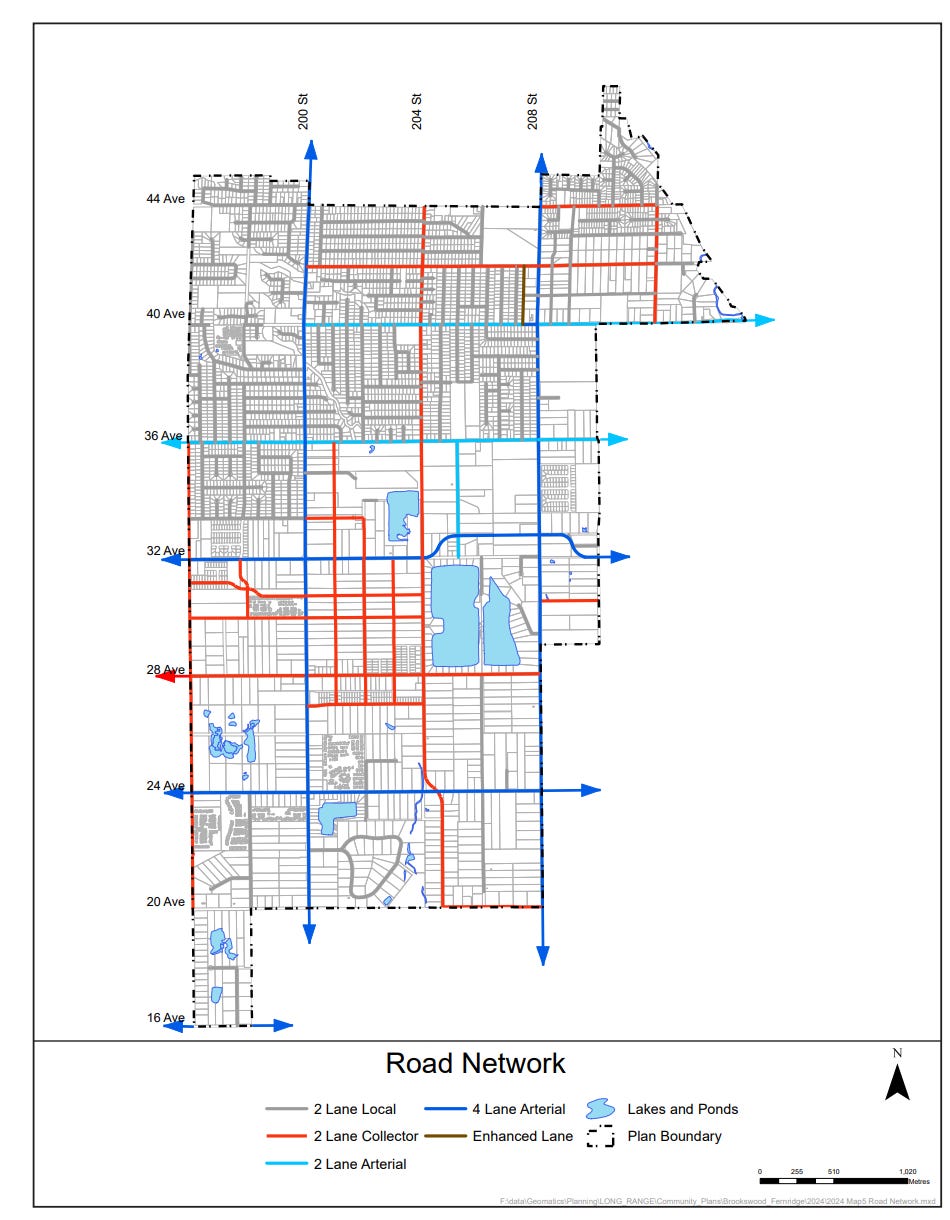

And if nothing changes, this trend is set to continue. Brookswood’s new neighbourhood plans, now approved, call for an expansive (and expensive) future road network of 4 lane arterials crisscrossing the neighbourhood.

Why?

Being Proactive

But it’s not too late. Now is the time to stop being reactive and start being proactive with our planning. Being proactive does not mean widening roads sooner, it means eliminating the need to even considering widening them to begin with. Being proactive with planning means taking steps to improve the planning process, and address these institutional and regulatory issues.

For example, with Brookswood, a more robust design process could force better collaboration between planners, engineers, experts and community members; something more like the Charrette process used in East Clayton would probably result in a much less car-centric more sustainable plan, and likely produce a better picture of what local residents actually want for Brookswood.

On the small scale, we could do something as simple as changing our zoning code to allow people to operate coffee shops and other small business out of their houses in residential areas. In residential zones, Japan allows 50m² (~500ft²) of floorspace to be used for business, creating neighbourhood amenities within walking distance.

Being proactive also means prioritizing updating the planning in areas around future rapid transit, as these are the areas which demand the least car-dependent infrastructure, and thus lower costs and better land use to build and maintain. As we talked about in our previous article, Vancouver’s Olympic Village is a great example to follow. This goes hand in hand with working with Translink to try and improve transit coverage, and also providing enjoyable and complete cycling facilities that can help get cars off the road.

We also need to not only allow more neighbourhoods to mature, but in a way that makes better use of the existing roads we have.

Projects like this one by the Higgins family in Delta are a natural intensification of land use as residential land prices continue to rise, however this is still illegal to build in Langley Township. Even though 4 units are now allowed by-right due to the province’s SSMUH legislation, this plan exceeds the 35% lot coverage restriction the Township has placed on most suburban single family lots if the original house is torn down. This could be changed.

The status quo isn’t working and, if it wasn’t clear from this post, I have growing concerns about this path we’re currently on. We need a vision for Langley that doesn’t push our community towards becoming a giant sea of asphalt and cars. There are plenty of examples locally, and around the world, that show us a better way is possible, and don’t require dramatic changes to move the needle.

If you’re interested in learning more about other people-oriented places in Canada and around the world mentioned in this article, I highly recommend viewing the Case Studies section of our website.

Strong Towns Langley is a community group dedicated to making Langley, British Columbia a better place. We advocate for incremental development, sustainable transportation solutions, housing accessibility, public spaces, and responsible growth strategies. Our group is part of the larger Strong Towns movement, focusing on creating financially resilient and people-oriented communities.

To learn more visit https://strongtownslangley.org